There’s an intense artificiality in the first act of Bound, where everyone has something to prove. Corky, released from prison, needs to regain both her financial and her social standing. Violet, a gangster’s girl, needs to recruit a hero to save her. And Ceasar… well, Ceasar doesn’t need to pose. At least not yet, but we’ll get to that in a minute.

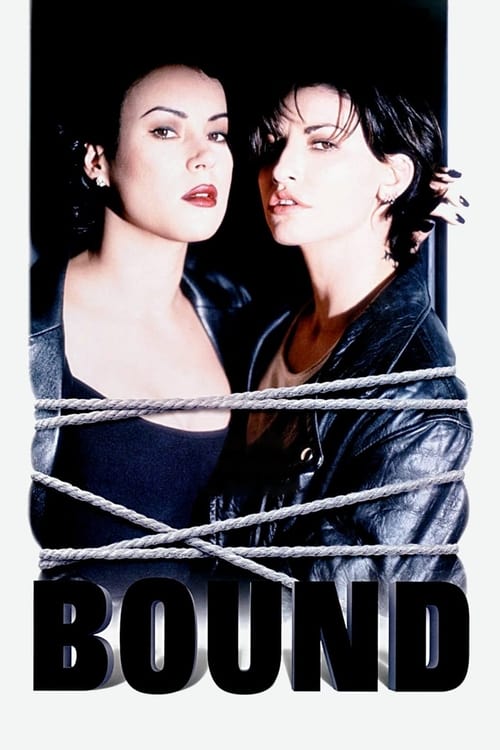

Gina Gershon has the cocky masculine street kid look down. For the first twenty minutes of the movie, Corky is all leer and sneer, slouch and strut. I found this off-putting, but that’s what this posturing is for — to create a sort of pre-emptive social exile in self-defense.

Jennifer Tilly’s Violet is disturbing; nakedly manipulative and cool, she wears “bubble-headed sexpot” like a cheap Marylin Monroe costume. Corky knows what she’s up to, and Violet knows Cory knows what she’s up to … but she’s going to play the innocent because she finds it amusing.

Corky is working next door to Violet and her mob-boyfriend Ceasar, cleaning up an apartment for a new tenant. It is filthy, sweaty work and Corky looks a mess. Violet knocks on Corky’s door with a couple of cups of coffee held up to her chest like small caffeinated breasts. She and her perfect makeup push her way into the apartment and lays the double entendres down thick. The Wachowskis put the action on the extreme left side. The right half remains empty. But as Violet’s aggressive neighborliness threatens to push Corky entirely out of the shot, the camera refuses to pull back. That right side gets more and more vacant.

“Does this bug you? I’m not touching you.”

It’s the first moment we see Corky flustered. Although she recovers — even overcompensates — we get to see the vulnerability beneath for an instant. This is where I realized the Wachowskis vision was more than hyper-cool, superficial noir fan-fiction.

In the Femme Fatales documentary included in my copy, Gershon says the tough, cocky masculine pose often hides very mushy vulnerability, and her difficulty was deciding when and how much of that to show through.

That’s less of a question for Ceasar — at least when we meet him. This is because Ceasar thinks he owns Violet, so Violet gets to see him at his angriest and his most threatened. Of Shelly, another mobster, Violet tells Corky “He was never afraid of Ceasar because he didn’t know him. Not like I do.”

“As you can see, I look much shorter than my girlfriend. I’ll have you know she’s two inches shorter than me. Don’t forget it.”

In a carefully shot and scripted scene typical of this movie, the Wachowskis show the power dynamics at work amongst the mobsters. As they torture Shelly — who they suspect of skimming from them — a distraught Violet declares she’s going to leave them to it. Ceasar wants her to say, which he makes clear in a way that sounds like pleading but masks a threat.

At that point, Mickey walks up behind him. “Ceasar, didn’t I tell you to get something?” he asks, and Ceasar scurries off. Turning to Violet, he says, “You shouldn’t have to see this. Why don’t you get outta here? Go for a walk.”

“Ceasar wants me to stay,” Violet says.

“Don’t worry about Ceasar,” says Mickey. “I’ll handle Ceasar.”

For Ceaser, Joe Pantoliano was told to draw inspiration from Bogart’s descent into Paranoia from Treasure of the Sierra Madre, and he’s more than up to the task. Even when Pantoliano isn’t in melt-down mode, he always looks on the very edge of it. It’s this performance that keeps the stylized, very colorful, dust-free world of Bound grounded in reality. Ceaser is our most reliable window into the fear, uncertainty, and doubt that plague all the characters; through him, we learn to look for the more subtle telltale signs in the others.

“Is Hitchcock there? I’ll wait.”

Most scenes are some combination of Gershon, Tilly, and Pantoliano together. It is an ensemble cast of character actors, and they work together well. Tilly takes special note of this: in Femme Fatales, she says played scenes with men that she was having an affair with that didn’t work. This despite the Wachowskis leaving little room for improvisation. Tilly says when she objected to lines, the Wachowskis would explain how they related to others later in the story. Eventually, everyone just trusted them.

That attention to detail extends well beyond the script to each shot of the film, which fits together like a puzzle. Unlike critics with a deadline, I write about movies weeks after I’ve seen them, which gives me a chance to let them bounce around (or not) in my head. With Bound I kept finding whole new themes or reads on the movie. The movie is about how we use artifice and pose to hide insecurity, I’d think. And then later I’d realize that much of the film was about the quality difference of loyalty inspired by fear over loyalty inspired by friendship.

Unusually for me — trained to study literature, not visual art — I also thought about shots. Much of what they do recalls Dario Argento, the great giallo director prone to cinematic excess, but Argento never seemed to care if the arty shot made any sense. The Wachowskis do. For instance, they set up one most dramatic shots much, much earlier, so what would otherwise be an arty shot seems to fit in the movie. It’s necessary for a movie that deals so much in the nuance of pose and authenticity.

Marketed on release as an erotic thriller, especially at a time where lesbian sex scenes in mainstream films were a novelty, Bound lasted a week in theaters. Tilly says they were all very conscious about not making a movie that was a soft-core exploration of lesbianism. That they did so with Dino De Laurentiis funding the movie was part miracle, part cunning. Tilly says the Wachowskis shot the (single) sex scene in one long, graceful crane shot to make it more difficult for De Laurentiis to shoot extra boobs and butts, then splice them in later on the sly.

For the sex scene itself — and the finer details of a genuine lesbian relationship, the Wachowskis turned to sex educator Susie Bright. The result was a film that served De Laurentiis’s expected thirsty hetero male audience rather poorly, but created a touchstone film for LGBTQ+ audiences.

However, after the first twenty minutes, the sexual orientation of the protagonists matters far less. This is not a movie about being gay; It is a con film, a crime film, a mob film, and a noir. It succeeds at these beautifully, and the film holds its own against other great classics in the genre. Both Tilly and Gershon say it is amongst their very favorite performances. It is one of my favorites.